A long, rambling mission statement

in which I admit I that need your help

WARNING: This post contains writerly soul-baring and navel-staring.

Never surrender

When it comes to writing, I am my own worst enemy.

I found a discussion thread on the forum page of my online writers group Codex yesterday, posing the question most writers must ask themselves at one time or another: when is it time to give up on writing? Spotting the title of the thread, I surprised myself with my furious, instinctive, all but visceral reaction:

NEVER!

There are no circumstances I can currently imagine that could move me to stop trying to express myself through story. Sure, I’ve had slow periods, I’ve been demotivated, I’ve at times claimed bouts of writer’s block, that widespread affliction I don’t actually believe in any longer. I’ve had years, particularly when our boys were baby boys, that yielded 5000 (5K) words in total, if that. There have been countless evenings and days off that I begrudged my writing the time I wanted to myself to wind down and not feel the countless demands modern life makes on me. I’ve doubted, wrestled, procrastinated, and flat-out refused to put my hands to the keyboard.

But the urge is never absent. Either I write regularly, or I feel the emptiness where the creative process lies comatose, the guilt of not doing what at least part of me believes I was made to do, the need that expresses itself as tense arms, worry lines, and wistfulness. Whatever else I may be doing, story is always at the near edge of consciousness. Every short, every novella, every novel that lies viable, promising, but unfinished, is an open wound.

Get a hobby

In the past, my struggle, my frequent reluctance, my guilt over not writing, have prompted my wife to ask if I should perhaps try a different hobby, one that brings more reliable enjoyment, and doesn’t feel so much like a chore at times. The answer to that, of course, that it’s not a hobby. Writing is a major part of how I define myself; in fact, up until I became a father, writing was the only thing central to who I was, or at least to how I perceived myself. (These days, I am a father, a husband, and a writer, in approximately that order.)

In the past, my struggle, my frequent reluctance, my guilt over not writing, have prompted my wife to ask if I should perhaps try a different hobby, one that brings more reliable enjoyment, and doesn’t feel so much like a chore at times. The answer to that, of course, that it’s not a hobby. Writing is a major part of how I define myself; in fact, up until I became a father, writing was the only thing central to who I was, or at least to how I perceived myself. (These days, I am a father, a husband, and a writer, in approximately that order.)

Granted, I’ve learned over the years to embrace the fact that I am also a highly skilled IT nerd, after struggling with that side of my self-image for decades. But I could give up computer work in a heartbeat if I had to; I can no more conceive of not being a writer than of not being a father to my marvellous children, or a husband to my incredible wife. I write not just because that is what I want to do most, but because that is what I am; I write because I can’t not write.

To write, one must write

Why, then, you may ask, do I do so little actual writing? I average perhaps two short stories a year, and manage to churn out a couple of novel chapters here and there; last year, when among other things I went and wrote half a novel (40K words) in three months on my commuter trains, was a bizarre outlier. The fact that I sell over half the stories I finish compensates slightly for my deplorable lack of productivity, but that’s not the point. The point is that I’m very passionate about writing, but do not actually write much at all.

Why, then, you may ask, do I do so little actual writing? I average perhaps two short stories a year, and manage to churn out a couple of novel chapters here and there; last year, when among other things I went and wrote half a novel (40K words) in three months on my commuter trains, was a bizarre outlier. The fact that I sell over half the stories I finish compensates slightly for my deplorable lack of productivity, but that’s not the point. The point is that I’m very passionate about writing, but do not actually write much at all.

Why not?

Being a father of two little children, I can believably claim time and energy constraints. And those were real, from our first pregnancy in 2009 up to early Spring of 2013, when our youngest finally learned to sleep through the night. It cannot be a coincidence that the 2013 outlier, that saw me writing 50K words of new fiction (including the half-novel I mentioned before) as well as 38K words of contest critique, followed hard on the heels of that incredibly energizing new period of not getting up in the middle of the night to prepare formula.

But while all of that is true, it cannot be the only explanation. For my difficult relationship with my own fiction predates our children by decades.

So what, then?

Nothing but a sorry phony

Part of the answer is the Imposter Syndrome. There was a great post on Facebook the other day about that, but I’ll give you a rather unrelated Tom Lehrer quote instead, which while not applicable at all, captures the spirit so well that it always makes me think of the IS–perhaps also because Tom Lehrer was so very skilled, not just at writing brilliant, hilarious songs, and mastering musical styles seemingly without effort, but also at not making a big deal out of it. I’ve never heard of an artist who was less enamoured with fame and success, less impressed with his own considerable skill.

Part of the answer is the Imposter Syndrome. There was a great post on Facebook the other day about that, but I’ll give you a rather unrelated Tom Lehrer quote instead, which while not applicable at all, captures the spirit so well that it always makes me think of the IS–perhaps also because Tom Lehrer was so very skilled, not just at writing brilliant, hilarious songs, and mastering musical styles seemingly without effort, but also at not making a big deal out of it. I’ve never heard of an artist who was less enamoured with fame and success, less impressed with his own considerable skill.

Anyway, the quote is: “He majored in animal husbandry, until… they caught him at it one day.”

The Imposter Syndrome is the erroneous belief that one has achieved, succeeded, progressed merely through a combination of sheer luck, beneficial misunderstandings, bluff, and being consistently overestimated by others. People suffering from this mental state are highly skilled at explaining away any and all of their achievements, pointing out the extenuating circumstances that let them pass beyond their abilities, minimizing their accomplishments, in the constant fear that someone, someday, will catch them out, expose them for the frauds they clearly are.

To paraphrase Mr Lehrer: “He met with modest success in his writing, until… they caught him at it one day.”

That proves nothing

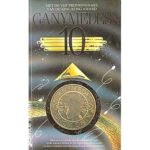

The first SF story I ever submitted anywhere, which I wrote in longhand after waking up with the plot at 4am when I was sixteen years old, was accepted and slated for publication in the foremost Dutch anthology of contemporary speculative fiction, Ganymedes. This acceptance should objectively have been a confidence boost, but the fact that the publisher discontinued the entire anthology a short time later held more sway in my mind. Sure, I was accepted, but for an anthology that wasn’t even commercially viable.

The first SF story I ever submitted anywhere, which I wrote in longhand after waking up with the plot at 4am when I was sixteen years old, was accepted and slated for publication in the foremost Dutch anthology of contemporary speculative fiction, Ganymedes. This acceptance should objectively have been a confidence boost, but the fact that the publisher discontinued the entire anthology a short time later held more sway in my mind. Sure, I was accepted, but for an anthology that wasn’t even commercially viable.

The first story I submitted after deciding to try my luck in the English language, sold to the first market I sent it to. Admittedly, the euphoria about this sale lasted at least two months. But it didn’t take me long to decide that the ten-dollar payment was sufficient evidence of the modesty of this achievement; reading my author copy of the magazine, I remember being unimpressed, and concluding that my own story was probably at the same level of mediocrity.

The second story I submitted, I wrote specifically for the market I sent it to, after a friend pointed the market out to me: Writers of the Future. Possessed of a deep level of naivité about the significance of that contest, my prime motivation was that it was the only contest I could find that did not charge an entry fee. I sent them my story on a whim, and found myself gasping for breath when they let me know that though I hadn’t actually won anything, they would buy my story for the next anthology anyway. My joy was sky-high, but the fact that it didn’t win stuck out a tad more in my eyes than the fact that it got published.

The third story I sent out made quarter-finalist in WotF, but collected eighteen rejections after that, until I had to decide it was time to trunk it. The rejections weighed heavier in my mind than the high ranking at WotF.

Still think you’re incompetent?

The fifth story I sent out won first place in Writers of the Future.

The fifth story I sent out won first place in Writers of the Future.

Now I must admit that was an achievement challenging my Imposter Syndrome skills to the utmost. One of the IS techniques, of course, is to cast doubt upon the context of the achievement, and that was the first approach I tried. This contest, after all, was established by the same man responsible for founding a semi-religious movement that is widely considered less than savoury, to say the least.

That didn’t work: not only does the Writers of the Future organization draw a strict demarcation line between the Contest and the other legacies of Mr Hubbard, the long, long list of past winners who’ve gone on to highly respected writing careers, and the long list of respected authors endorsing the Contest, speak for themselves.

So maybe the quarter in which I placed first was a weak one? That thought held up until I read Vol.XXI of the anthology, containing my story and the other winners. I was in awe of all the other stories; if the judges, all writers I respected, had placed me above two of these tales, there was no longer any way I could fool myself into maintaining that Meeting the Sculptor was a mediocre story that just managed to sneak in under the radar.

Sculptor must be a good story, and by extension, I must at least be a competent writer.

This paralyzed me for years.

The open door

I sometimes claim that the Writers of the Future win came too early in my careerlet, that I wasn’t ready for it, that I got my wish too soon, that having my dream fulfilled of that moment in the spotlight, that award ceremony, that bow-tied penguin suit, I was left floundering. And all of that is sorta true, even.

I sometimes claim that the Writers of the Future win came too early in my careerlet, that I wasn’t ready for it, that I got my wish too soon, that having my dream fulfilled of that moment in the spotlight, that award ceremony, that bow-tied penguin suit, I was left floundering. And all of that is sorta true, even.

But I’ve grown to believe that the truth is more complicated.

Having to accept that I have the makings of a skilled writer, that I am competent enough to write an award-winning story, that I may even know what I am doing, terrified me into creative paralysis. Because there is a second factor in play that works together very well with the Imposter Syndrome, one that had joined hands for decades with my urge to tell stories: the need to be seen, to receive encouragement, to gain outside approval from authority figures.

Stemming from a huge reservoir of fundamental insecurity, this need drove my creative process, to the point where every story wasn’t just a story, but a shout-out to the people whose approval I most desired: see, here I am! This is my work! Look on my works, ye mighty, and rejoice! However, ye mighty never much rejoiced at all (a fact reflected painfully on a larger scale in the lack of interest in my international achievements in my own country). Next to story itself, the desperate need to be seen was always a deeply seated driver for my writing.

The huge, objective, outside confirmation that the Writers of the Future win represented to me, however joyful, threatened all that. It threatened to force me to abandon my need for approval, instead holding a beckoning door ajar to a new world where I might simply rejoice in my own skills, embrace my successes, loudly crow my own achievements.

Where I might simply believe in myself.

That door is still open, and the other side still beckons. But it’s a scary door to pass through, because while the light on the other side is gorgeous and tempting, it’s also blinding: it illuminates more clearly the things I know on this side than what’s waiting for me on the other side.

Through the door

Much of what’s on the other side I already know.

Much of what’s on the other side I already know.

I’ve been a member of the Villa Diodati Expat Writers Workshop for years now, and every time I attend one of our workshop weekends, I feel less like an intruder, less like an imposter, and more like I actually do have the skills and the credits to be among that wonderful group of funny, talented, (and gourmet) writers as an equal. But the doubt nags, the Imposter Syndrome lurks, the need for affirmation lingers, and the one snide remark one of the members made three years ago about a less than impressive semi-pro sale I reported, still sometimes outweighs the wonderful feedback the group has given me over the years.

And I’ve grown more active within the Dutch specfic community, and met many wonderful kindred spirits in that context, and made dear new friends, and received acknowledgements aplenty for the things I’ve done with my writing. But that is a community better versed in criticism and low-key comments than in positive feedback; the acknowledgement I still believe I need is hard to come by there.

My foot is fully through the door, and I know in my head that the other side has more room for growth, and more joy, and just generally a higher standard of living as a writer, even though the work will still be as hard, the struggle will still be there. I’m wavering on the threshold, holding on to the familiar gloom and self-limiting delusions on the side I come from.

High with a little help from my friends

I need–and I choose that word with great care–I need to drag my other foot through that door, take a final, irreversible step, embrace, not fear, that I believe in myself. I need to stop holding myself back, to stop seeking safety in the familiar. To dive courageously into the unknown. I need to face those demons, those authority figures that held such sway for so long by withholding their approval for so long, face them if only in my mind, and defeat them as Sarah did the Goblin King, through that handful of words, that simple formula, that self-confident spell, spoken in wonder as much as determination:

But to quote another of my musical heroes, Bruce Springsteen, on his Live In New York City album (imagine a broad, rough voice sweeping a huge crowd like a pentecostal preacher): “You can’t get to those things by yourself! You gotta have help!”

Which is to say: any encouragement is greatly appreciated.