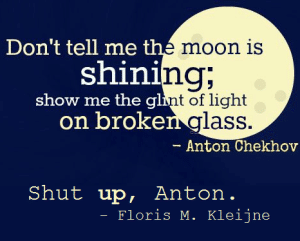

An evil dictator has taken over the realm of writing critique. She has held sway for years now, if not decennia, and has cowed writers both green and experienced into near-blind obedience. Her dogma has become the staple of writing feedback, to such an extent that reviewers fear to leave out her central tenet:

An evil dictator has taken over the realm of writing critique. She has held sway for years now, if not decennia, and has cowed writers both green and experienced into near-blind obedience. Her dogma has become the staple of writing feedback, to such an extent that reviewers fear to leave out her central tenet:

Show, don’t tell.

I say it’s time we strike back at this fundamentalist bitch, overthrow her rule, and take back what has always been, and always will be, the primary right of every writer: the right to tell.

I have three arguments to underpin this counter-revolution.

1. Show Is Slow

Now, you won’t catch me arguing that SDT is wrong, not just because it would incur the wrath of Dontellia, but mainly because SDT is sound advice—and usually good feedback to receive on a piece of fiction.

However, there is such a fault as too much of a good thing. Take, for instance, this bit of scene:

His heart pounded as sweat mingled with his regulation crewcut. Every little sound made him twitch. The shadows seemed to hide dark and hideous things. The muzzle of his M16 danced to the rhythm of his shaking hands.

What the author is really saying here, of course, is:

He was really scared.

Now, obviously the first bit is far better fiction. However, it’s thirty-eight words long, and the condensed, horribly telly version has all of four words. This may be an extreme example, but there are countless places in your fiction where you’re better off sacrificing show for the brevity of tell.

2. Your Protag Got No Show

This one holds true in particular if you’re writing in close third POV, or even in first. Let’s take this telly fragment:

She could see the goon was lying to her.

Showing, instead of telling, this might become:

As the goon reported to her, his eyes shifted left and right. He fidgeted with his hands, and when he came to the crucial part, he let his gaze wander up and left.

Admittedly, I’m no expert on non-verbal cues that someone is lying, so bear with me. For the sake of argument, let’s stipulate that this is an accurate description of someone displaying all the non-verbal cues that he’s lying. (Further on, I’ll claim to be the world’s leading expert on the topic.)

Who says my female protag is consciously aware of them?

My protag may be a private dick used to working her cases by gut instinct, relying on hunches and feelings without ever being aware where those originate, how she comes to her conclusions. To her, all she is aware of is the feeling that the goon is lying. Showing the reader what she is seeing, and thus allowing the reader to draw his own conclusions along with my protag, is in fact a major POV break. In this example, therefore, telling is way better than showing.

And in general, protagonists will jump to conclusions from subconscious observations much more often than they will be aware of exactly what they’ve seen. In all these situations, telling isn’t just the best approach, it’s the only approach if the author wants to stay true to the chosen POV.

3. Your Reader Don’t See The Show

Take the previous example. Let’s say I’ve exhaustively researched the non-verbal cues to lying, and watched every single episode of every single season of Lie To Me a dozen time, and am now the world’s foremost experts on the subject, able to describe in exquisite and exceedingly accurate detail the facial tics, mannerisms, hand movements and shoulder shifts that cue in my heroine that the goon is lying. Let’s say I use that research to write the perfect showy scene of the goon betraying himself for the lying bastard he is.

Who says my reader will pick up on it?

This is my most fundamental objection to Dontellia’s tyranny. Show-Don’t-Tell is a writerly thing, an obsession obsessed over by authors only, and not at all something a reader necessarily cares about or even picks up on.

So I’ve written that perfect non-verbal, non-telly description of a lying goon, and my reader goes: “Huh? What was that all about?” And whoops, there goes my scene, the point is lost, the reader tosses my book, and my career goes down the drain.

So next time Dontellia attempts to enforce her rule with an iron fist, I propose we authors stand up to her, and gently—and if necessary forcibly—point out to her that there is a tremendous amount of grey between the white of Show and the black of Tell.

Down with Dontellia! Up with common sense!